In Australia a lot of wines are produced as straight varietals, however, most of the world’s bench mark wines are actually blends. Discussions continue about blending versus straight varietals, often regarding Old World (Europe) v New World (Australia, USA, NZ, South America and South Africa). Many Old world wine regions are regulated regarding allowed varieties and blending components, but this is not the case in the new world. For Australia these differences in approach were cemented further in 1994 with a trade agreement with the European Community. It determined a list of protected names (such as Claret and Burgundy) that, following a transitional period, would not be permitted on Australian wine labels. Other countries made their own agreements with the European Union, but Australia was one of the first to make a concerted effort to quickly adhere to the new agreement. In removing the protected names Australian labelling focussed on varietal naming instead. It was quite a radical move and helped create a point of difference for our wine. However, some people believe the attention on single varieties has ignored the benefits of blending.

Each region in France has its own regulations on which varieties are allowed for that region. For example, in Chateaneuf-du-Pape (in the Southern Rhone) there are eighteen allowed varieties but the blend is usually made up of Grenache, Mataro and Shiraz, with Grenache generally dominant. The beautiful Charles Melton Nine Popes (Barossa Valley) is based on the Chateaneuf-du-Pape style (he developed the name from an adaptation of Chateaneuf-du-Pape which means “New Castle of the Popes”). By the way, if you’re thinking of going to the village of Chateaneuf-du-Pape in your flying saucer you’d better think again. In 1954 a decree was passed to ban any flying, landing or taking off of flying saucers in the village! There had been UFO sightings reported across France and locals were concerned that they may have a negative impact on their wine.

Italian regions also have some regulations regarding blends and varieties. A Chianti Classico, (Tuscany) has the dominant variety of Sangiovese. In the past it was blended with Canaiolo and other red varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, plus the white varieties Trebbiano and Malvasia. It was only in 1996 that the regulations changed to allow wineries to produce a straight 100% Sangiovese.

Often the labels on Old World wines do not declare any varieties because people just know what the varieties are based on the region that it is from. We do not have that same history here so our labels have been more informative and consumers have relied on that. Did you know that when you are drinking an Australian Shiraz or Cabernet there may be up to 15% of another variety in there? To label a wine as a single varietal you need at least 85% of that variety; the remaining 15% can be anything.

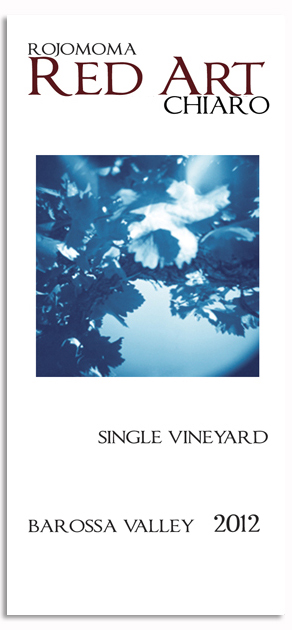

The information to include on the label is an interesting point. Going back to Charles Melton’s Nine Popes, the front label doesn’t have any varietal information on it, but he has successfully marketed the story of the wine. To blend or not to blend…is that the question? This argument is possibly the wrong one to be having. Perhaps it’s more about the marketing of the wine and whether the focus should be on what the wine actually delivers – what its personal story is. We all know a Shiraz from one winemaker can be completely different to that of another, even from the same region. When I released my Chiaro earlier this year I was nervous that it might be difficult to sell because  the name and the wording on the front label indicate nothing about the variety. Although it is a straight Shiraz, I made it in such a different way that it is nothing like a Barossa Shiraz, and nothing like my normal Shiraz produced from the same vines. So I chose not to refer to the variety to avoid being misleading about its style. I have been very happy to see the Chiaro selling well and to witness interest and love of this wine because of its style, and not because it’s a Shiraz.

the name and the wording on the front label indicate nothing about the variety. Although it is a straight Shiraz, I made it in such a different way that it is nothing like a Barossa Shiraz, and nothing like my normal Shiraz produced from the same vines. So I chose not to refer to the variety to avoid being misleading about its style. I have been very happy to see the Chiaro selling well and to witness interest and love of this wine because of its style, and not because it’s a Shiraz.

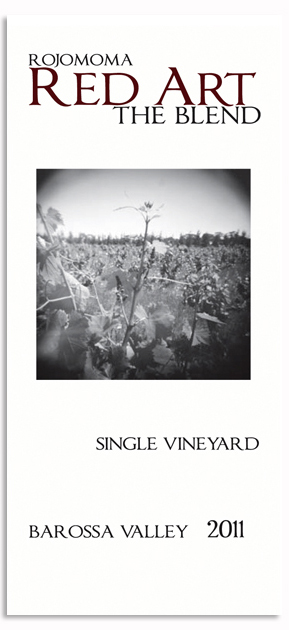

Red Art The Blend

Red Art The Blend 2011 is a blend of Shiraz, Cabernet Sauvignon and Petit Verdot. It was m atured only in older oak, and released soon after bottling. This means that it was a little cheaper to produce, so I have been able to price it lower than my other wines. After a year in bottle the three varieties have integrated really well together and the tannins have softened beautifully. The Blend 2011 has earthy, savoury flavours with plum, violet and cocoa. I took the photo for the front label with my beloved Holga camera. Using medium format film, it is a plastic camera with a plastic lens. Its ‘dodginess’ creates light leaks and vignetting (the dark corners) and a surreal feel which I really enjoy.

atured only in older oak, and released soon after bottling. This means that it was a little cheaper to produce, so I have been able to price it lower than my other wines. After a year in bottle the three varieties have integrated really well together and the tannins have softened beautifully. The Blend 2011 has earthy, savoury flavours with plum, violet and cocoa. I took the photo for the front label with my beloved Holga camera. Using medium format film, it is a plastic camera with a plastic lens. Its ‘dodginess’ creates light leaks and vignetting (the dark corners) and a surreal feel which I really enjoy.

Some labels of interest: